For me, the fantasy genre has always been a mixed bag of pleasures. For every tasty chocolate truffle of pure imagination (Lev Grossman’s exemplary The Magicians, for instance), there are three or four of the cheap Hallowe’en candy no one likes, the post-Tolkien ‘orcs and trolls’ variety a la Ed Greenwood, wherein each novel reads like a particularly dense night of playing Dungeons & Dragons.

While I appreciate the effort such authors take at expansive world-building, I find that fantasy works much better when it is incorporated into a more familiar world, using fantasy to enhance the reality of recognizably human characters. Clive Barker, Jeff Vandermeer, Susanna Clarke and the aforementioned Grossman weave tales of wonder I wish would never end. And Tim Powers? I’ll have to read more of him to make sure, but based on reading his recently re-released 1989 novel The Stress of Her Regard, this guy is the real deal.

Stress follows the adventures of Michael Crawford, a young doctor in England in the 1800s. After his new bride is brutally murdered while he slept next to her, Crawford finds himself ‘wedded’ to a nephelim, a vampire-type creature that has claimed him for her own. Crawford flees, and subsequently becomes an acquaintance of such famous Romantic figures as Percy Shelley, John Keats, and Lord Byron, all of whom also have had dealings of some kind with the supernatural world Crawford now realizes swirls all about him. The Nephelim, while jealous and possessive to the point of murder, also enhance artistic expression in their partners, a double-edged sword for poets such as Shelley who are addicted to the creativity their unnatural spouses allow them yet despair as their earthly loved ones die about them. Powers crafts a secret history that underlies the world of the 1800s, wherein magical elements have had a profound impact on many of the major figures of the time.

This is not ‘easy’ fantasy; this is dense, intricate work more akin to ‘hard’ science-fiction in its approach to its subject matter. If you are easily befuddled by sentences such as “This phantom and the sphinx evidently each existed at specific intensities of the time-slowing they’d been experiencing—each of the apparitions only became visible or invisible as a viewer approached or receded from its characteristic point of the time spectrum,” you’re going to find Stress a grind of a read. Stress also defies easy categorization, being at any one time a historical fiction, a fantasy, a vampire novel, or all three at once. It brings in elements of Egyptian, European, and Middle Eastern mythology, resulting in a sometimes-breathtaking literary epic of scope and grandeur.

I won’t say that I loved The Stress of Her Regard unreservedly. I often got lost in the labyrinth of the plot, and was as often befuddled as I was astonished. But Powers has erected a complete world of dense and mythic proportions, one that is at once familiar yet completely alien. Stress may not be the easiest read, but it is a deeply rewarding one.

VERDICT: MONKEY LIKES

by Ann & Jeff Vandermeer (eds.)

Steampunk, for those out there unfamiliar with the genre, is usually defined as an alternate reality fiction that combines elements of the Victorian era with more advanced technological developments of the modern age, although usually, as the name implies, powered by steam. It is an often rich and intricate world, allowing authors to travel the realms of historical fiction while at the same time adopting the tropes of science fiction. And its acceptance into the mainstream is gaining steam, so to speak. From early works (H.G. Wells and Jules Verne are usually cited as progenitors of the genre) to more modern authors such as China Mieville, William Gibson (who alongside Bruce Sterling may have written the definitive steampunk novel,The Difference Engine) and Jay Lake, steampunk is definitely catching on. Young adult novels such as Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, Stephen Hunt’s The Court of the Air, Scott Westerfeld’s upcoming Leviathan, and Arthur Slade’s terrific The Hunchback Assignments are bringing a whole new generation into the fold.

It is a tricky procedure, but when it works (as in my personal favourite, Paul Di Filippo’s Steampunk Trilogy), the result can be gloriously entertaining.

And Steampunk, an anthology edited by the esteemed duo of Ann and Jeff Vandermeer – Jeff is the author of City of Saints and Madmen, a bizarre and twisted fantasy/sci-fi collection you should all read; he’s also one of my closest Internet friends, i.e. a man I’ve corresponded with but never actually met in the flesh (incidentally, Jeff has recently worked on a slideshow of the history of steampunk, and it is worth checking out) – is indeed gloriously entertaining stuff. Gathering together some of the masters of the category (including Di Filippo), the Vandermeers have attempted to bring some terrific examples of this burgeoning world to light.

Things get rolling with an example from one of the godfathers of the genre, Michael Moorcock, with an except from his Warlord of the Air. If I had to choose a favourite, my choice is the entry by the multi-talented Joe R. Lansdale (see next review below for more). His "The Steam Man of the Prairie and the Dark Man get Down" is by far the most visceral and disturbing piece in the collection, a vivid sequel of sorts to H.G. Wells' The Time Machine, following the exploits of the time traveller after he has ripped open tears in the fabric of reality and has harnessed the Morlocks to terrorize the world. Discomfiting stuff, but gripping. Molly Brown switches the tone to the delightful, positing a sequel to Jules Verne's From the Earth to the Moon. Brown's "The Selene Gardening Society" presents a plan to return to the moon to plant gardens for the benefit of future explorers. Ted Chiang's "Seventy-Two Letters" mixes in Kabbalistic magic and the myth of the golem, resulting in one finely-tuned piece of weird imagination.

There are far more wonderful pieces, including authors as diverse as Michael Chabon and Neal Stephenson. Steampunk is an extravagant treat, a celebration of literary invention, and a perfect introduction to a rapidly expanding genre.

VERDICT: MONKEY LIKES A LOT

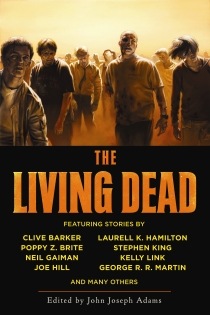

by John Joseph Adams (ed.)

by John Joseph Adams (ed.)

I loves me my zombies. Don’t know why. Don’t care to know why. But ever since a young me caught Night of the Living Dead on A&E (in the days when it really was about arts and entertainment, and not the reality filth-fest it’s sadly become), I have been hooked. Watching those fuzzy b&w monsters assault that house. Poor Barbara. And the ending? Ben, surviving a night of unthinkable horror, shot by excitable rednecks. For the first time, I became acutely aware that happiness was not a requisite part of an ending.

Since then, zombie movies have been a pleasure of mine, sometimes guilty, sometimes not. I winced and squirmed in the best way through Lucio Fulci’s Zombie, and winced and squirmed in the worst possible way through Uwe Boll’s House of the Dead, a movie so idiotic that it is far funnier than many comedies (sorry, Kira). I declare George A. Romero's Dawn of the Dead to be one of the greatest horror movies of all time, the remake surprisingly good, Romero's Day of the Dead uneven but memorable, and that remake even worse than House of the Dead. And I can only pray that patron saint Romero regains his balance with his newest opus Survival of the Dead, if only to wash away the bitter taste that was his Diary of the Dead (oh what a waste!).

But for me, zombie novels have been a mixed bag, with nary a classic in sight. Brian Keene makes a valiant effort, but his novels quickly become repetitive and sorta dull. David Wellington is a good talent, but Monster Island was too much Resident Evil-style video game action and not enough actual horror. World War Z was good, in some places excellent, and while I await the movie with much gleeful anticipation, it didn’t wholly overwhelm me. Stephen King’s Cell was half a great zombie novel, and half kind of meh. Pride and Prejudice and Zombies was a passable literary mash-up that quite frankly needed more zombies and less Austen. I withhold judgement on Robert Kirkland’s graphic series The Walking Dead, as I have not yet finished the last three books (but up to book seven, I’ll say the thing is damn awesome).

But The Living Dead fills the nooks and crannies of every literary need I’ve ever had (where they pertain to resurrected corpses, anyway). John Joseph Adams’ anthology of previously released stories hits so many high points I grew tired of counting them.

Even I’ll admit that zombies can be tiresome; not much personality, kind of slow, easily defeated on a one-to-one basis. Certain liberties must be taken with the mythos to make such creatures interesting over the course of 400+ pages, but Adams puts in just the right mix of classic monster mayhem and mythological experimentation to make the whole of The Living Dead an absolutely spectacular collection. There is everything a zombiphile could want; gore, satire; parody, gore, emotion, comedy, gore, sex, nostalgia, and gore.

I can’t possible list every favourite moment, but there are a few standouts even among all the excellence. Dan Simmons, an amazing writer whom I hope returns to horror very soon, starts off the collection with a bang with “This Year’s Class Picture.” A teacher, driven almost mad, continues to try and teach a class of dead students while the world collapses around her. Grim, gruesome, and sensitive, Simmons’ tale hits all the right classic moments. “Death and Suffrage” by Dale Bailey takes the collection into satire, envisioning a world where the dead arise during a presidential election and begin to exercise their right to vote (Joe Dante adapted Bailey’s story into the vastly entertaining “Homecoming,” an entry in the Masters of Horror anthology series on Showtime). Nina Kiriki Hoffman’s “The Third Dead Body” veers the anthology into romance and obsession, albeit of the most unsettling sort. Maestro’s Clive Barker and Stephen King contribute some early classics of their work. Darrell Schweitzer’s “The Dead Kid” rivals King in his mingling of childhood innocence with horror. “Those Who Seek Forgiveness,” Laurell K. Hamilton’s first story with her heroine Anita Blake, is so strong I’ll have to overcome my initial prejudice to her Vampire Hunter series and give them a try. Joe R. Lansdale (again!) moves the zombie into western territory with “Deadman’s Road.” “The Song the Zombie Sang,” by the formidable team of Harlan Ellison and Robert Silverberg, may be the most exquisite and beautiful story involving a zombie ever published.

Enough raving, I’m starting to sound like an undiscerning fanboy here. Suffice to say, The Living Dead is everything I’ve ever wanted in the zombie genre.

VERDICT: MONKEY LOVES, UNCONDITIONALLY, WHOLE-HEARTEDLY

8 comments:

Too bad you weren't in town last month. Lori & I got to sit in on the sound mixing for the last ten minutes of "Survival of the Dead", thanks to a friend of ours who is a friend of Romero's (and a zombie in the big finale), with drinks with Romero & company at the bar next door. It was lots of fun.

You're killing me, you know that, you are literally KILLING ME!!!!!

Our friend, Robert, is the guy dead centre in this teaser poster that showed up a few months back.

"John, we need a more crunchy sound on that scalping... Try mixing in some velcro..."

I hate you, I hate you, I hate you. What's next? Hey, Corey, i ad dinner with James Morrow and William Kotzwinkle last week. AUGH!

Next is joining Robert and possibly (though not probably) George for the Zombie Walk and an outdoor screening of Night of the Living Dead in Dundas Square on Saturday. Unfortunately, we weren't able to get tickets to the Survival of the Dead showing at TIFF.

Ooh, I've got to find The Stress of Her Regard. Sounds kind of like Chariots of the Gods for Romantic poetry lovers...

have you seen Peter Jackson's zombie film Braindead (Dead Alive here in Canada)?

It's hysterical, and the most bloody movie ever

as in they used more gallons of fake blood in it then any other movie

I have indeed, and love it unreservedly as well. Bless its gory little unbeating heart.

Post a Comment