It is to much to hope that every great writer's first attempt will be a home run. Sure, Joseph Heller catch-phrased American irony with Catch-22, Harper Lee moved us to tears with To Kill a Mockingbird, and John Kennedy Toole changed the world (or my world, anyway) with A Confederacy of Dunces. But for every astonishing debut, there are innumerable debuts that only hint at greatness to come. John Irving's meandering Setting Free the Bears. Neal Stephenson's self-indulgent The Big U. Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.'s Player Piano, a good book that only hinted at how truly astonishing its creator could be. And let us not forget Brian Horeck's Minnow Trap, the worst novel ever written (I realize Boreck is not considered a great writer by anyone, but I couldn't come up with a more-memorable example).

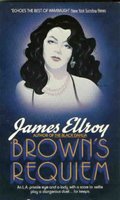

And so it is with James Ellroy. His later works such as L.A. Confidential, The Big Nowhere, and American Tabloid are breathtaking masterpieces of the darkest criminal noir. Ellroy's never having been awarded a Pulitzer Prize is one of modern literature's great oversights.

Yet Brown's Requiem, his first novel, barely whispers the spectacular heights Ellroy is capable of. Where his later works (most specifically his L.A. trilogy) combine grotesque crimes, gnarled plots, and dialogue so hard-boiled it leaves bruises, Brown's Requiem displays all the hallmarks of an author struggling to find his voice.

The plot, it must be said, is the weakest element, a limp mix of Hammett, Chandler, and every other influence a novice writer may try to emulate. Fritz Brown is an L.A. detective/repo man who unwittingly becomes embroiled in a bizarre case involving arsonists, welfare fraud, crooked cops, sexy dames, heroin, and many other standards of the crime thriller. As Brown tries to sort out the mess, he begins to view the overall case as his chance to make a change in his life.

So far, so good. No one ever said a plot had to be overtly original to be entertaining. The greatest detective novel ever published, Raymond Chandler's The Long Goodbye, has very little plot at all. What matters in these cases is style, voice, and attitude. Chandler had it in spades. Current Ellroy wields attitude like a bludgeon. Early Ellroy is all pose, no threat.

Part of the problem is the anachonistic tone Ellroy sets up. Brown is set in 1980 (very late, for Ellroy), yet the story reads like something set in 1950. It's the way the characters talk, the use of dialogue like "Do your stuff, Daddy-O," and "Onward, Hot Rod," and so forth: for whatever reason, the fact that this story takes place in 1980 is never remotely believable. Perhaps this is why Ellroy's later works are unabashedly nostalgic for the fedora-and-cigarette world of 1950's Los Angeles. Ellroy's L.A. of 1950 is effortless; his L.A. of 1980 is faintly ridiculous.

All this sounds like an out-and-out pan, but it's not; Brown is still quite entertaining, with a labyrinth of a plot and a firm grasp of what drives a scene, and is worth a read by those familiar with the ouvre of hard-boiled detective fiction. If nothing else, Brown's Requiem could serve as an example of how much an author can improve, given time. Ellroy is one of the finest novelists in America today. Comparing his newer efforts to his earlier ones only serves to prove it.

1 comment:

Ah, there's hope for us all!! Great review!

Post a Comment